At the British School of Coaching (BSC) we are proud of the quality

of all our programmes, including ILM Level 7 programmes such as Level 7 Certificate and Diploma in Executive Coaching and Mentoring, Level 7 Certificate and Diploma in Coaching Supervision. Level 7 qualifications

are designed to be consistent with Master’s level qualifications of

higher education (MA, MSc, MPhil).

BSC learners benefit from studying

in small groups with 1 to 1 personal tutor support, one area of

discussion is; “what is meant by critical analysis”?

The requirement to be ‘critical’ is a key component of level 7

qualifications, for example to critically analyse or review. Ofqual

(which regulates general and vocational qualifications in the England)

provides Level 7 descriptors, as follows:

For knowledge and understanding, the descriptor includes requirement

that the learner: “Critically analyses, interprets and evaluates complex

information, concepts and theories to produce modified conceptions.”

(Ofqual, 2015, Qualification and Component Levels Requirements and

Guidance for All Awarding Organisations and All Qualification, p 8)

In relation to skills, the descriptor includes the requirement that

the learner is able to: “Critically evaluate actions, methods and

results and their short- and long-term implications.” (Ofqual, 2015,

Qualification and Component Levels Requirements and Guidance for All

Awarding Organisations and All Qualification, p 8)

Over the years we have learnt that sometimes learners struggle with

the requirements of Level 7 assignments and assessment. For example, we

may find the following written exchange on the mark sheet for a Level 7

assignment:

Assessment Criterion – ‘Critically assess the contribution of coaching to improve both individual and organisational performance.’

Feedback – ‘You have provided a detailed description

of the contribution of coaching to improve both individual and

organisational performance, but there is limited critical assessment.’

In a recent debate hosted by the organisation Intelligence Squared in

Sydney Australia, and aired on the BBC, a member of the panel,

Professor John Haldane, Professor of Philosophy, University of St.

Andrews, opens the debate by suggesting “the capacity for critical

engagement and reflection is diminishing. He went on to say “we used to

say I disagree and this is why…. We now say I feel and I am offended”.

Professor Haldane went on to share his observations, which he described

as a trend that if you disagree with the prevailing view there is less

likely to be a space to present your thinking, your critical review and

arguments. This made me think of examples when the popular view becomes

the ‘right’ one. I wonder is this because individuals follow the

feelings rather than listening analysing the evidence and reflecting?

I also wonder whether the space to listen and reflect has reduced

through the need for an answer. If we are not seen to have an instant

view on something we are thought less off. I have experience of clients

who shared examples of feeling under pressure to provide an immediate

answer without being allowed an opportunity to consider the reasons for

and against. One client described this as “it isn’t fashionable to

think”. I wonder whether immediate decision making is considered

efficient and therefore productive? That if the majority have a certain

opinion it must be the “right”, almost out sourcing our critical

thinking to a third party. This reminds me of times, when I have said,

“this idea must have been thought through” – I can’t be the only person

who’s said this? Whilst I recognise the good stuff of information

sharing on social media I also think the instant nature of it creates

emotional followers rather than informed followers or informed thinkers.

So thinking critically requires deeper thinking, we need time to

think. But first what does ‘critical’ mean, in this academic context?

And how does it differ from description?

First, to dispel some common misconceptions – being critical is not

being negative, condemnatory or simply pointing out what is wrong with

something such as an idea, a theory, or evidence.

Thinking positively, here are some definitions of what being critical is:

• “Being thoughtful, asking questions, not taking things you read

or hear at face value. It means finding information and understanding

different approaches and using them in your writing”

(www.ed.ac.uk/institute-academic-development/postgraduate/taught/learning-resources/critical).

• “Critical thinking is the process of applying reasoned and

disciplined thinking to a subject….. You will need to develop reasoned

arguments based on a logical interpretation of reliable sources of

information”

(http://www2.open.ac.uk/students/skillsforstudy/critically-processing-what-you-read.php).

• “… a form of intelligent criticism which helps people to reach

independent and justifiable conclusions ..” (Moran AP (1997 Managing

Your Own Learning at University, University College, Dublin, quoted in

University of Bradford Academic Skills Advice Critical Analysis – So

what does that REALLY mean”)

These definitions (from the University of Edinburgh, the Open

University and Bradford University) are complementary and to me the key

points are:

• understanding information

• reasoned and disciplined thinking

• questioning and challenging

• evaluating information

• developing your argument

• drawing conclusions

Let’s look at these in turn.

• Understanding. Before you can be critical of

anything you have to be really sure you understand it – whether it is a

theory, a model, an idea, an aspect of coaching practice, research

evidence. Usually, when writing critically you will need to describe

(say what it is in some detail) the ideas, models, theories, evidence

that you are going to be critical of.

• Reasoned and disciplined thinking. This is a development from understanding – now you really understand the ideas think about them logically and carefully.

• Questioning and challenging. Don’t take what

you read or hear at face value – question if the information is valid

and reliable, is there bias in the information, are conclusions

supported by the evidence provided, was the methodology used to collect

the evidence appropriate, could there have been a conflict of interest

between the author and funding body? Show why the information you have

used is relevant and appropriate – is it up-to-date? If not, will this

undermine its value? Is the information from a reliable source – e.g. a

peer-reviewed journal or an established academic authority?

• Evaluating. Come to a judgement on the

strengths and weaknesses of the information (whether your or other’s

research findings, theories and models from the literature, your own

ideas) you have described; this can also involve weighing up one piece

of information against another.

• Developing your argument. This builds on the

reasoning, questioning and challenging – develop your argument using

logical interpretation of information.

• Drawing conclusions. What are the implications

of your analysis and interpretation of the information? To go back to

the initial example, can you conclude that coaching makes a positive

contribution to personal and organisational performance? Is coaching

generally effective but with limitations? Or has your analysis of the

information led you to conclude that coaching is no more effective than

standard performance management?

Conclusion

The key differences between a ‘descriptive’ piece of work and ‘critical’

writing is that the former simply demonstrates what you know. The

latter demonstrates that you have thought about what you know

sufficiently to be able to make a judgement about the information and

draw conclusions from it.

Further reading:

Series of guides and tips from University of Bradford Academic Skills Advice

Series of guides from University of Edinburgh Institute for Academic Development

Guide on critical writing and a guide on critical reading from University of Leicester

Intelligence Squared

Friday 22 April 2016

Tuesday 12 April 2016

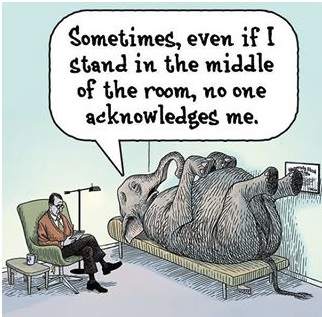

The content of a coaching session: the art of elephant spotting

|

| Martin Hill, Senior Tutor BSC |

Sounds easy doesn’t it? A lot of the coaching models that you will be familiar with also give that impression – for example GROW – the first item on the agenda is to identify and agree the goal. Unfortunately, the first declared goal may not be the real goal – in other words the elephant has not yet been spotted. This may be for a variety of reasons – the coachee may feel nervous; feel a sense of shame or a fear of failure – it may even be the case that the coachee is unsure or uncertain.

Here are some of my tools and tips that I have gleaned from my own coaching and supervisory practice and which help ensure that the elephant is spotted and appropriately dealt with:

• Preparations – the pre-session contact and information that you forward to the coachee can play a critical role in scene setting, managing expectations and providing the foundations for building trust and rapport. How do you “contract”? Including the coachee in the process and exploring their preferences/ expectations pays dividends in this regard – for example establishing their learning style preference (which enables the coach to plan for that) or establishing their understanding of, and tolerance for, challenge.

• Confidentiality – you know that you have established trust and rapport when the coachee feels confident to disclose personal, often their innermost, thoughts and feelings. The greater the attention you pay to explaining confidentiality, and agreeing the boundaries thereof together, the more likely it is that the elephant will come out into the open. Remember though that elephants do not like shocks or surprises – beware of promising “total confidentiality” as there are things that may arise that require disclosure and if you have not fully explained this or checked for mutual understanding – the elephant may well stampede and retreat into the distance.

• Patience – relax and be prepared to play the long game. Each coachee is unique and will have their own bespoke coaching experience. Bear in mind as well the nature of the coaching engagement as this may be a contributory factor in making the coachee feel safe and relaxed – for example internal coaches may notice that it takes longer to establish total trust and rapport with internal coachees, compared to external coachees.

• Check-In To Check-Out – even if the goal/topic has been identified and the session is focused on this, take the opportunity from time to time throughout the session to “check in” with the coachee and “check out” that this remains the most pressing or relevant goal or topic that the coachee needs to discuss.

• Questioning – Use of clear and focused questioning can help unearth the true issues. In “Enabling Genius” (2016), LID Publishing Ltd Myles Downey outlines that one of “the means of managing one’s thinking …is called the ‘floodlight and spotlight’. Floodlight comes first. Floodlighting shines light on the whole territory and into every nook and cranny. It includes what one notices, what one thinks about, what one intuits, imagines, feels and desires. Floodlight is followed by spotlight and the best question to focus the spotlight is: what stands out? Or what is most interesting? Cliff Kimber…asks this question frequently: ‘What do you need to think clearly about?’” Think of this in relation to your coaching practice – does your questioning generate floodlight and spotlight thinking?

• Use the AWE question – “The Coaching Habit” – Michael Bungay Stanier (2016) Box of Crayons Press uses this tool – the AWE question is (drum roll please)… “And What Else?” This can even be used at the goal/topic discussion stage – do not just accept the first declared goal, follow it up with AWE!

• Intuition – as your confidence as a coach grows, you will notice that you are becoming more adept at sensing or feeling (a “gut reaction”) the non-declared topics/issues. This intuition is something to pay attention to, but always needs to be carefully managed. Always seek permission to check out if the intuitive sense is accurate, and/or is something that the coachee is content to explore.

• Observation – the elephant in the room may be spotted by your observations – not just visual but also active listening. For example you may notice discordance in body language or expressed emotions by the coachee when they are talking. Another concept to be aware of comes from Hawkins & Shohet’s Seven Eyed Supervision model – “parallel process”. This could include the situation where the coaching session with the coachee mirrors how the coachee acts/behaves normally –sometimes contradicting what they are telling you in the session. It may be useful to explore this with the client by asking them to describe how they approach a task etc. The coach would then highlight what they have observed and the discordance. For example one coachee was describing her frustration with her second in command and spent some time explaining what the coachee was doing to address that and expressing confusion and frustration at the fact that it was not working. The session was interrupted by a knock on the door and I had a ring side seat and was able to hear the interaction between the two. When the session resumed, I played back what the coachee had initially described about her own behaviours and actions and contrasted that with the interaction I had just overheard which evidenced the complete opposite! A powerful tool which worked wonders.

• Use of knowledge – as the coach you may come into possession of knowledge or information that is unknown to the coachee. This is where Johari’s Window can be a really powerful tool to use and help the coachee explore their own “blind spot” and the “unknown” arena as well.

• Materials- Have you got everything that you need – pen, paper? Sometimes using a different learning style or using creativity in the session can expose the elephant. For example a coachee struggled to talk about an emotional issue; until I suggested that we tried a visual representation of the subject – hey presto! Make sure you keep your “coaching kitbag” stocked and also make sure that you keep it current and topical to suit your practice.

• Challenge – be ready to challenge the elephant in the room – especially if it has not been “noticed”, or acknowledged by the coachee.

• How do you eat an elephant?

Make sure you deal with the elephant by setting small “baby” steps for action – make sure that they are SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time bound) and get the coachee to visualise and describe what the successful completion of the action will look and feel like , what will others notice; what will people be saying etc.

• Suspend Judgement – maintain neutrality no matter what is disclosed. Simply acknowledge, accept and explore.

I hope that this has provided a catalyst for your own thoughts and reflections and I would be interested to hear from you with your own comments or observations (email Martin@britishschoolofcoaching.com).

Sunday 10 April 2016

Endings in a Coaching Relationship

|

| Martin Hill, Senior Tutor BSC |

In this blog I thought it may be useful to draw on the lessons I have learned from my own coaching and supervisory practice relating to endings in a coaching relationship.

Ironically, before I explore the topic of endings, I need to look at beginnings. Stephen Covey (“Seven Habits of Highly Effective People”) highlighted that Habit Two is “Begin with the End in Mind”. What does that mean? www.businessballs.com (accessed 25/03/16) states “Covey calls this the habit of personal leadership – leading oneself that is, towards what you consider your aims. By developing the habit of concentrating on relevant activities you will build a platform to avoid distractions and become more productive and successful.” Ok – so what does that mean for you as a coach? For me, it means ensuring that your coaching preparations lay the foundations for the whole of the relationship, including planning the ending phase-but more on that later.

Enough of the beginnings, already – let’s get to endings. The title of the blog is not a typographical error – as a coach you may encounter a variety of endings in the course of a coaching relationship. In the course of a recent group supervision discussion I facilitated at a British School of Coaching UK Coaching Network, asking the group of coaches what they understood “endings” to mean, generated the following insights:

• The end of a topic/goal discussion within a session, so that the discussion moved to the next topic/goal

• When, and how, to draw a session to an end (linking in to time management of the session)

• The ending of the coaching relationship itself – this prompts me to pose the following questions for you, dear reader, to reflect on for your own coaching practice:

– Was the ending planned or unplanned?

– What was the catalyst for the ending?

– Who ended the relationship –coach or coachee?

– How was it ended?

• How does one know when a goal/objective has been achieved and thus can be ended? How are outcomes reviewed? Who is involved in that review-coach alone? Coachee alone? Coach and coachee? Coach, coachee and organisational sponsor?

The other nervousness highlighted when discussing endings with my coach supervisees, is how to actually deal with the topic of ending with the coachee. One approach is what I describe as the “It’s not you, it’s me” style conversation. Even writing that phrase, I could feel the aftershock-like tremors of memories being jogged by the earthquake shock of painful reminiscences of long ago relationships!! Remember having those conversations, or being on the receiving end of one? How did that feel? How long before you stopped dissecting the ins and outs?

One of the risks of the “It’s not you, it’s me” style in a coaching relationship is that it masks the real reasons for the ending. If you are operating a professional and ethical coaching practice, I am sure that the values of honesty, openness and transparency are of fundamental importance to you. The ending will be easier for you and the coachee to deal with if it is discussed in an open, objective and evidenced fashion. For example – “Our discussions about topic x, are outside my field of experience and I think that a different coach with that knowledge may be more useful for you. I may be able to help you with finding that coach if you would like.”

What about another approach? Remember my promise to return to the planning phase? When I am agreeing my coaching contract/agreement with the coachee and organisation I ensure that my planning includes anticipating potential endings. This means that we agree who, how and when can terminate the coaching relationship. Notice anything missing from that list? My contract does not specify grounds/examples for the coaching relationship to be terminated. This is because I identified that this could be a barrier to the issue being raised, especially for the coachee potentially, and this in turn would mean that the effectiveness of the coaching relationship would be diminished. However, it’s YOUR contract and YOUR choice what goes in to it.

The other feature in my coaching contract/agreement with the coachee and organisation, and which I draft together with them, are what I describe as my “expectations” section. I outline what the coachee/organisation can expect from myself as the coach (and sometimes specify what it does not include, e.g. I am not here to provide advice to you) and also what I expect from them as coachee/organisation – e.g. punctuality; to turn up with pen and paper; to take ownership for the agreed actions.

The beauty of the coaching contract/agreement approach is that this provides a depersonalised mechanism to review the effectiveness of the relationship and discuss and decide if ending is appropriate. The contract/agreement can focus on behaviours that were agreed, but which have not been honoured etc. As a coach, I find that this gives me a mechanism to challenge the coachee and this usually serves as a prompt to bring them back on track.

Here are some of the factors that I have noticed that help build an effective and successful framework for dealing with endings within the coaching relationship:

• Contracting – Take time to identify all the players involved as there may be a multiplicity of parties- for example, coach, coachee, sponsor (HR), line manager, department head, organisation etc. etc. This also influences what documentation may be needed – for example the “formal” legal contract (dealing with fees, deliverables, termination, confidentiality etc.) needs to be agreed with the “sponsor”, but I also ensure that the coachee in these situations completes a coaching agreement which outlines what they can expect from myself as the coach, what is expected of them, confidentiality and termination and cancellation). Think what may be needed for your own practice. Review your coaching agreement/contract. Does it cover what they can expect from you as the coach and what is expected from them as the coachee? Does it cover termination? If not – what are you going to do?

• Values/beliefs – Let me paraphrase a quotation “To coach others, you must first know yourself”. Not only do you need to ensure that you know your own values and beliefs, you must make sure that your practice and behaviours are consistent with them- this can often avoid unexpected endings from arising in the first place.

• Know when to say “No”- If there is no beginning, there can be no end – so be clear who you decide to coach and/or be clear about what actions you are prepared to undertake as coach (e.g. notes; chase ups; out of session contact etc. etc.).Reflect on those choices and challenge and review them regularly.

• “Permissions”- If in doubt, ask – seek permission from the coachee to check things out. Really useful, for example, when dealing with the outcomes review. I would recommend that as a minimum this should be done by the coach and coachee together; but why not also consider inviting the line manager/organisational representative to part of the review session, with the coachee’s permission. (See my blog on permissions here)

• Regular Reviews – earlier in the blog I mentioned planned and unplanned endings. A planned ending could arise where you have agreed to undertake, for example, five sessions. A good practice to develop is to introduce regular reviews, mine, for instance is after every 3rd session. This is simply a quick “coaching MOT” check – are you content with the relationship; does anything need changing; are actions being generated? Is value being added? If the answers to any of these are negative then this is a prompt to recontract and agree, or, to agree to end the relationship. Unplanned endings can, as the name implies, arise at any time. The same approach of discussing and recontracting or agreeing to end the relationship.

• Boundary Management – make sure that you know the boundaries for your own competence- and do not overstretch. Also make sure you do not stray into counselling or advising mode. I would also suggest reflecting on the hypothetical situations when you would decide that you would have to end the coaching relationship. Review those situations – are they covered in your coaching contract/agreement? If not – time to review and revise.

• “I’m OK, You’re OK”- endings can be emotional – make sure that you check that the coachee is ok and can get back ok. Similarly, give yourself time to review, recollect yourself, reflect and reboot.

• Location – This links in to the topic above- if you anticipate that the relationship may be coming to an end in the next session, especially if you anticipate emotional or difficult responses, plan where and when to hold that session – the primacy concern being that of safety for yourself and the coachee.

• Supervision/Support – Endings can generate emotional responses- both conscious and sub-consciously. Reflect on the support networks you have to draw upon (supervision, peers etc.) – is anything else needed or are these sufficient? What did you do to recalibrate? Could that be used again? Could that be improved?

• Adopt a 3R Evaluation Approach – Review, Reflect & Revise – following each coaching session that you conduct, seek feedback from the coachee, but also take time to review the session, reflect on what you did and what the effect was; also consider what worked well, what could have been improved on or what could have been done differently. Finally, if the reflection leads you to conclude that something needs to change, and then revise your approach before the next session. Does the ending generate the need to review and revise your coaching contract/agreement or coaching approach?

I hope that this has provided a catalyst for your own thoughts and reflections and I would be interested to hear from you with your own comments or observations.

In my next blog, I will look at the content of coaching relationships and the art of elephant spotting!!

For more blogs like this visit www.britishschoolofcoaching.com/blog/

Labels:

coach,

coaching,

endings,

mentor,

mentoring,

permissions,

relationships,

review,

support,

values

Friday 8 April 2016

Beginning a Coaching Relationship

|

| Martin Hill, Senior Tutor BSC |

In this blog I thought it may be useful to draw on the lessons I have learned from my own coaching and supervisory practice relating to the beginning of a coaching relationship with a new client.

Frequently coaches say that they achieved rapport and gained trust, but when asked what they did and how they did it, they frequently are unable to do so. This can even apply to experienced coaches. The risk as one becomes more consciously competent is that complacency can begin to creep in and we begin to take some skills and behaviours almost for granted, meaning we give them less focus and attention. I would recommend taking some time to review and reflect what you do and consider how you managed to create a safe environment that helped to build trust and rapport.

Here are some of the factors that I have noticed that help build an effective and successful coaching relationship:

– Preparatory Actions- Even before the first session is held, your preparatory actions can be critical in building a sense of trust and rapport with your coachee. Do you always follow up your potential leads? How is that done? Have you got your “elevator pitch” fine-tuned? Prior to a first session I forward my coachees a copy of my profile, a brief explanation about what coaching is, a copy of the proposed coaching contract/agreement and a copy of the Code of Ethics I follow. The advantage of that is that the first session spends minimal times on dealing with these “administrative” necessities, and the majority of the session is focused on coaching. The pre-session material outlines what the coachee can expect of me, and also the expectations of them.

– Research Preparation- taking the time to research the coachee and/or organisation is something that can potentially reap huge dividends- not only does it illustrate a professional and committed approach, but it can provide you with background knowledge that can be used to make the coachee feel at ease and relax, once they realise that there is some element of common understanding. Some coaches take this a stage further and ask the coachee about their preferred learning style or their “challenge” preference/tolerance. This can enable the coach to adapt their coaching style to accommodate those preferences. Bear in mind, however, that sometimes it is useful to “stretch” someone by choosing a different style – but that is something that is likely to be more productive once the coaching relationship has had time to establish.

– Contracting- Again this is a preparatory element – who do you have to contract with? This could be a 2 way contract (between coach and coachee directly) or a 3 way contract (coach, coachee and sponsor). Take time to scope all the players involved as there may be a multiplicity of parties- for example, coach, coachee, sponsor (HR), line manager, department head, organisation etc. etc. This also influences what documentation may be needed – for example the “formal” legal contract (dealing with fees, deliverables, termination, confidentiality etc.) needs to be agreed with the “sponsor”, but I also ensure that the coachee in these situations completes a coaching agreement which outlines what they can expect from myself as the coach, what is expected of them, confidentiality and termination and cancellation). Think what may be needed for your own practice. Finally, this may also assist with who should be invited to attend the first session – I have found it useful to invite , having discussed with the coachee, the line manager so that the coachee and line manager can both hear me outline what will happen in the session and critically, what confidentiality means- which helps build trust as the coachee knows there is not going to be a separate conversation between coach and line manager ( which could create doubts or concerns about what will be discussed at that meeting) and also means that the line manager and coachee are clear about what the coaching sessions will focus on, which avoids misconceptions and misunderstandings arising.

– Chemistry Session- some coaches offer “chemistry” sessions or calls so that coach and coachee can discuss preliminary matters and establish whether they can work with one another. Some coaches offer the first coaching session as a “free” session at which they cover similar matters to those outlined in “preparatory actions” above- explaining what coaching is; dealing with the contract etc. This can be done face to face or by telephone or Skype.

– Location- This depends on how the coaching intervention is going to be conducted – it could be face to face or it could be done remotely via telephone or Skype. Whatever the method, ensure that the coaching room is a “safe” environment – not just for the coachee, but also for you. Make sure that the room is comfortable and that interruptions can be minimised, if not entirely avoided. Make sure that you get there early to set the room up to ensure that the coachee feels relaxed and focused.

– Dress- wear something that helps you feel comfortable, relaxed and professional. It is worth checking as well with the coachee, if you are coaching at their organisation’s premises, whether they have a particular dress code that needs to be followed.

– Materials- Have you got everything that you need –pen, paper, laptop, charger etc.? Make sure you keep your “coaching kitbag” stocked and also make sure that you keep it current and topical to suit your practice.

– Authentic Self- Edna Murdoch once said “Who You Are Is How You Coach” – [2010] Personnel Zone. Make sure that you are behaving as your natural self and being true to your values and beliefs. Sometimes assumptions and presumptions can be made by a coach about what they think the coachee is expecting about how they behave and act and this can lead to the coach overcompensating or undercompensating their own skills and behaviours. If you are not being true to self, not only will you feel uncomfortable – but the probability is that the coachee will notice – at the very least it will affect the session flow and feeling of naturalness.

– Adopt a 3R Evaluation Approach- Review, Reflect & Revise- following each coaching session that you conduct, seek feedback from the coachee, but also take time to review the session, reflect on what you did and what the effect was; also consider what worked well, what could have been improved on or what could have been done differently. Finally, if the reflection leads you to conclude that something needs to change, and then revise your approach before the next session.

I hope that this has provided a catalyst for your own thoughts and reflections and I would be interested to hear from you with your own comments or observations.

In my next blog, I will look at the ending of coaching relationships.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)